Embracing the Spirit of Training

I like to joke that my training plan has a soul. I’m not really joking.

Hello. Whether you are a runner or not, rest assured that there is no actual training advice in here. You will walk away with as much (or as little) understanding as you had about periodization models and intensity distribution, having learned nothing about weekly mileage, interval length, or long run duration. Below this paragraph, it’s all personal experience, thinking out loud, and some weirdly strong opinions about fonts.

It’s finally here: the most wonderful time of the year. A time of celebration and anticipation. A time to reflect on the past and set new goals for the future; to snuggle on my favorite chair, a steaming cup next to me and a laptop on my knees, in front of a festively color-coded spreadsheet filled with nothing but possibility and hope.

I’m talking, of course, about the beginning of the training season, which I kick off by sitting on my butt in front of a screen for a prolonged period of time.

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy the actual training—all the ups and even the inevitable downs. Out of doors and out of breath, that’s my jam. Yet, the planning and scheming (and dreaming) that precede it are pretty jam-worthy, as well:

Unlike the execution of training, the training plan is invulnerable to circumstance—there’s a whole expression about things being “perfect on paper.” And while, like other such purely theoretical concepts (time travel, the perfectly ripe avocado, etc.), this idealized version of training may not manifest in the empirical world, its elusive nature invites speculation, exploration, and experimentation.

What all of this means, and the reason I can’t help but feel drawn to this unattainable perfection: Potential. Not even potential for anything specific, but the mere possibility that things that currently aren’t, could be.

Right now, it’s all in the future: The good—any conceivable improvements resulting from training are still hypothetical; and the bad—I’m yet to sleep through my alarm, get a weird niggle, or eat something I shouldn’t. Everything is so wonderfully uncertain.

Yes, it occurs to me that “uncertain” typically carries a negative connotation. I am aware, too, that it means things can go wrong just as easily as they can go right. The potential is equally for a breakthrough or disaster (or both).

Except, a training plan is, by its nature, optimistic, in that its very existence is predicated upon the belief that it’s worth following. To me, its purpose is twofold: to create space—not a formula—for positive change; and then to guide me in the general direction of good things happening (a successful race being one, but not the only, such good thing). When something inevitably goes wrong (and given enough time, something will), The Plan will get me back on track and prevent a downward spiral.

For that, it needs to be adaptable. More on that in a minute. First, it needs to be pretty. I mean easy to use.

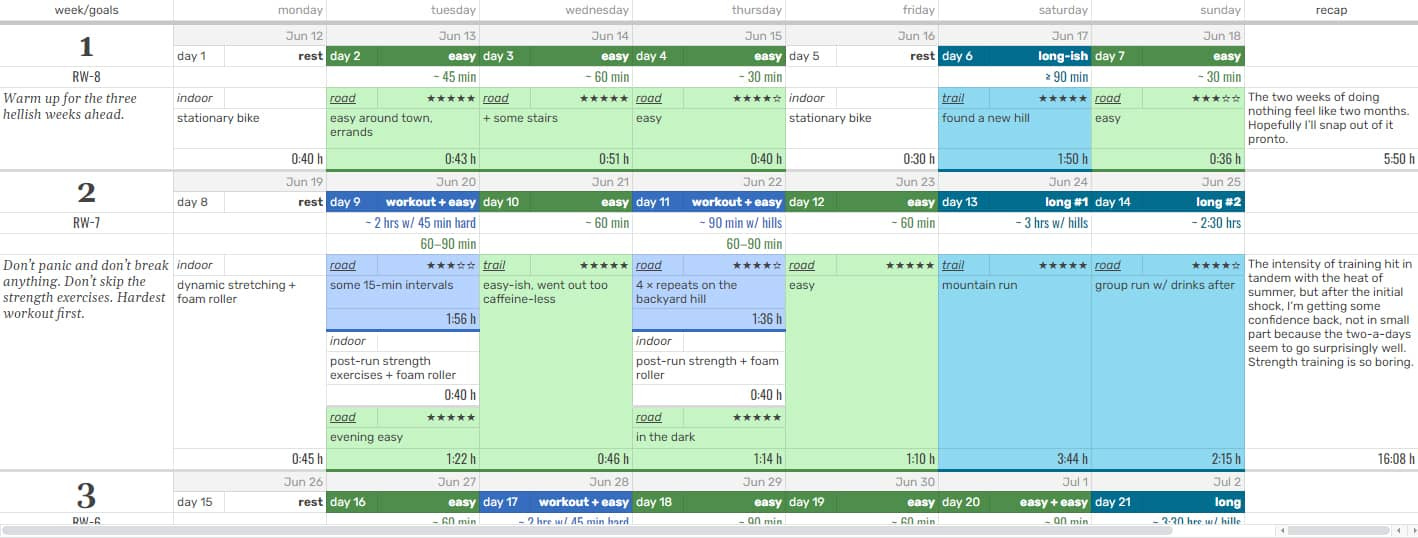

I spend a lot of time formatting my spreadsheet. I’m told being a huge nerd has something to do with it, but no, it’s much worse: I am a connoisseur of tabularly organized data. I could just slap some dates and numbers in 10-point black Arial in there, perhaps make the race day in red, and be done with it. I could also run in cotton underwear and ill-fitting shoes, but that ain’t happening either. It has to feel right. That means a well-organized layout, visual hierarchy, color consistency, detail. And no freaking Arial.

Perhaps that’s too much time to invest in an effort of questionable utility, but I mean, come on—ultrarunning.

Plus, creating my spreadsheet is rewarding in itself. It gives me the sense of making progress before I actually start making progress. Not to mention, I consult previous years’ spreadsheets quite often, so it’s nice when they aren’t aesthetically grating. Before I share how I structure my training plan, please enjoy this Reading Recommendation in a Single Quotation with No Further Explanation:

❝Oftentimes, we don’t have the capacity to recognize our own personal growth or decomposition—it’s a realization that’s reserved for reunions, weddings, and funerals. Occasionally, though, it’s drastic. The flu, followed by dehydration, long miles, and rising temperatures, chiseled away at the last of my fat and into my muscle. In a culvert, beneath the Loneliest Road in America, the abyss was staring back at me.

—Rickey Gates, Cross Country: A 3700-Mile Run to Explore Unseen America

planning my training: more spirit, less letter

I begin by being ardently enthusiastic and unconditionally curious about the sport for a number of years, which provides enough understanding of training principles (📚), as well as invaluable experience (🏃🏻♀️), to ensure that what I call a training plan isn’t just blind guessing with a chance of shin splints.

That done, I open up my spreadsheet, enter the race date, and then number the weeks between now and race week (in a large, juicy serif). Groundbreaking stuff. Depending on how many of those weeks there end up being, I consider what types of goals I can realistically set for the race. I then make sure those goals are S.M.A.R.T.1, P.U.R.E.2, or otherwise subject to acronymization. No, not really.

Some of my friends are surprised when I tell them that I have no intention of trying to win; that 99 percent of the participants have no intention of trying to win; that the remaining one percent will have had time for a shower and a long nap by the time I finish; and that, yes, I will still do the race. It’s embarrassing having to explain my entering a competition with no hope of winning. Embarrassing for my friends, I mean. Poor them, they don’t realize that racing isn’t just for the winners anymore. The regret for their mistake is plainly evident on their faces as I explain at length and in great detail about Only Competing with Yourself, A Sense of Accomplishment, and, of course, Fuh-uhn.

Like my racing, my training is not that of a winner. I could never run as much as the elites do and still have a heartbeat. But, based on the modest, middle-of-the-pack goals I come up with, I can design a very rough training schedule that works for me.

It is ridiculously easy to fill those little table cells with promises. Intervals and hill repeats—intimidating, but I know I’ll get through them because I always have. Long runs on weekends—naturally. I’ll strength-train, of course, and do mobility exercises. Drills are important, too, and let’s not forget foam rolling. Surely I’ll make time for all that and pay attention to sleeping well and eating healthily.

Yeah. Perfect on paper. In practice, “something” will happen, “life” will get in the way. Hell, I’ll probably get in my way. So I build my plan to be adaptable by following these two rules:

I set weekly, not daily goals, and never for more than two to three weeks ahead. Typically, it’s one.

“Weekly goals” are things like focusing on a particular intensity or adaptation, or simulating race-specific conditions. No numbers. After all, it’s not just numbers I’ll have to deal with on race day. Example: “Train with a full pack in the heat.”

This column is set in friendly, serif italics—the typographic equivalent of my running partner calling to say he’s headed toward our usual meeting spot. A familiar voice with just the right amount of urgency. My typical response to both spreadsheet and person: “I’m on my way, and I’m bringing snacks.”

And if, for some reason, I can’t make it that day or even the next… I don’t sweat it too much, as long as I keep the focus on my weekly goals (and as long as those goals don’t literally include the aforementioned heat acclimation, in which case I sweat quite abundantly).

I do have some numbers elsewhere in my spreadsheet for things like distance/duration and total time at a given intensity. They’re not targets per se, but for the most part, I do adhere to an approximation of them. They’re set in a robust, condensed typeface that resembles the one on my watch. And they all have a “≥” or a “~” in front of them. It’s my way of telling myself to cool it with the parking lot loops (translation for non-runners: this is when you run in small circles at the end of your run so you can finish with a nice round number on your watch; there is no known way to make this appear as the rational behavior of a sane person).

The third and final important section in the spreadsheet is the “recap” column, where I summarize the week that has just passed—sometimes in several lengthy paragraphs, and other times in just a telegraphic sentence or two. Behold the eloquence: “got covid. legs no run. fingers no type good.” This was January 23 through 29, 2023.

And that’s it, that’s how I build my training plan. I hesitate even to keep calling it a plan, as it increasingly seems more of a training… direction. As the months wear on, I’ll nail some workouts and bungle others, while most of the running will happen far from the extremes. Things will fall into place in that fashion, week by week, until I reach the bottom of the spreadsheet.

don’t call it a resolution

Is it too late into January to do a take on “New year, new me”?

I’ve heard many times that a race is the celebration after the hard work, and it’s true—in the same way it’s true that we don’t live 364 days of the year just for the fireworks on New Year’s Eve. Honestly, I often forget about the race altogether. I just keep planning my weeks one at a time, doing my workouts, and dealing with “somethings” and “life” as best I can.

And for some reason, my best is better when there’s a race on the horizon, regardless of whether I consciously think about it or not. Once I’ve fallen into the routine of my commitment, I become more motivated to solve things, and I pay more attention to things, and, paradoxically, I find more time for non-running things.

And that, right there, is why I don’t like starting my training on January 1. See those wonderful changes non-exhaustively listed above? Can you spot the New Year’s resolutions trying to wiggle their jolly way in?

I’m not big on those, but even if I were to make some, I wouldn’t want them equated or even correlated with my training/race goals. To me, running is a continuous thing that ebbs and flows naturally, on its own, with ups and downs and beginnings and endings inherently embedded into the experience of it. It generates its own celebrations, too. It doesn’t need New Years, birthdays, or other temporal landmarks3 supposedly separating the person who was from the person who will be; it’s all the same person. I get the idea of turning over a new leaf by disassociating from whatever unwanted past behavior, but as far as running is concerned—gradation over disruption, resilience over renewal.

P.S. As

rightly pointed out, I did not provide a visual for the reader to feast their eyes upon. So here’s a screenshot of my spreadsheet from last June:Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed your time here, please share “Embracing the Spirit of Training” or this newsletter with a friend. Then go pet a dog, ignoring the owner.

Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound.

Positively stated, Understood, Relevant, Ethical.

Hengchen Dai, Katherine L. Milkman, and Jason Riis, “Put Your Imperfections Behind You: Temporal Landmarks Spur Goal Initiation When They Signal New Beginnings,” Psychological Science 26, no. 12 (November 5, 2015): 1927–36, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615605818.

You talked so much about your lovely spreadsheets, but as long as you don’t show us one of them, I don’t believe anything in this text 😂

The current version I'm telling myself of "a race is the celebration after the hard work" is "you've already run 80% of the ultramarathon when it starts"