Hello. I have words for you again. Fair warning: Some of them rhyme. Badly.

This is my second post on the whys of ultrarunning—you know, those whys everybody says are so important to have. This time, because of their unexpected gifts. And it’s also a story about that time I got to stand on the podium (a rare occurrence), and all I could think about was how my bedsheets smelled wrong.

Why Ask Why? was the double-post with which this series began and will eventually never end. The first ultrarunning why I attempted to understand was ‘To Find My Limits.’

a snooze i couldn’t refuse

“This is going to be my slowest 100k ever.” Twenty-two hours in, my race wasn’t going so well. I was behind schedule due to an unusual amount of snow on the course, and a last-minute course change had just added a 40-minute insult to injury. In addition, I had a directional problem: my feet wanted up in the air, my butt wanted down in the snow, my food wanted up my esophagus, and I was so sleepy I couldn’t think straight.

I had expected all the falling, even the nausea. But the heavy eyelids caught me by surprise.

What a luxury it is to suffer through a hardship of one’s own choosing; to be able not only to fail with minimal to no consequences, but also succeed by one’s own definition of success.

In the little bubble of amateur endurance sports, it’s the amateur endurance athlete who gets sole ownership of that definition. The effort required by these events is far too great for its worth to be determined by any but our own version of success—one not meant to bow to objective criteria but holding within it a personal reason to keep coming back.

I had run through the night many times. I had once watched the daylight fade and then welcomed it back twice in the span of a single race, with not a minute of sleep. So it was not I who had planned this nap in the woods—it had been planned for me by an entire day of traveling and insufficient sleep the night before the race.

Despite my disappointment at having to lose yet more precious minutes, I still believed this could end up being a successful race. Not in the sense that some deus ex machina-esque twist could make my time goal realistic again, no; but in the sense that, at this moment, I simply didn’t know what would turn out to have been worth the effort.

And later that day, I did know. The answer, which came in the form of a trophy, was this: not a trophy.

Sometimes, even we get surprised by what success looks like from behind the finish line.

run fast, never finish last?

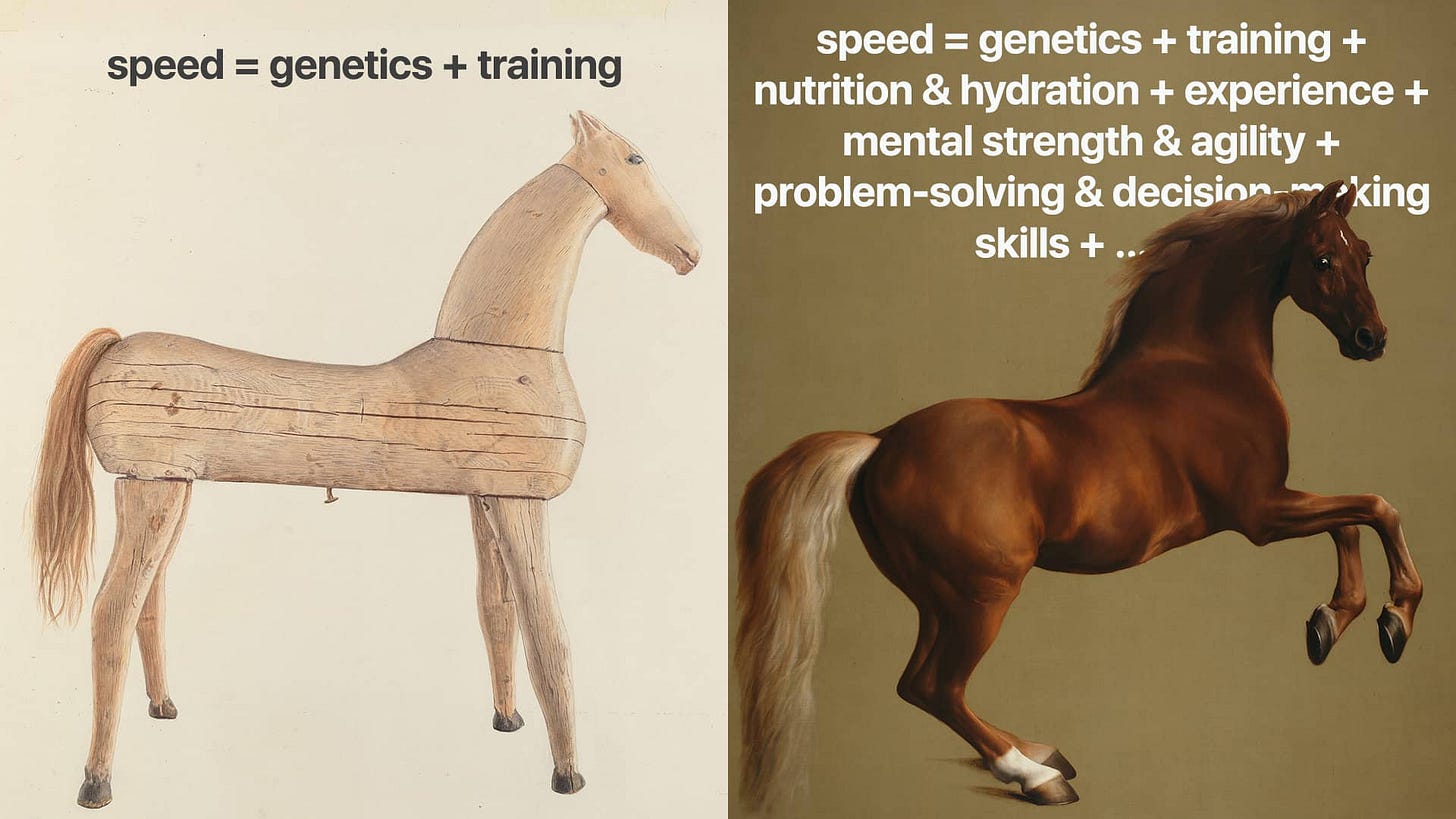

A footrace, as the name suggests, is a race between your feet to see which one is faster. Or, okay, if you want to get strictly lexical about it: A race is a contest of speed. And speed is simply a product of genetics and training—or is it?

Not in any but the shortest of races, and definitely not in an ultramarathon. Ultra speed is a complex and dynamic combination of, yes, genetic ability and relevant training, but also a whole list of other factors, which lengthens with the duration of the race.

The beauty of this more complete formula for speed lies precisely in its complexity. And by “complexity,” I mean brain stuff.

cerebrate to celebrate

Ultrarunning is a sport of the mind as much as it is of the body. I don’t usually like to refer to those as separate things, but in this case, a differentiation might help emphasize just how big a role our psychological fitness plays in these events: managing effort; maintaining focus and perspective; identifying physiological cues; “reading” the environment; adapting to unexpected changes; making decisions on the spot in unideal conditions; developing strategies; anticipating outcomes; regulating emotions; and more. Talk about a cerebral six-pack. All of this, of course, only compounds the inherent physical toll of hours upon hours of moving… actually pretty slowly.

And so it is that, in endurance sports, mens sana comes together with corpore sano to create a new form of speed: efficiency. Wasting nothing and taking advantage of everything—that’s the stuff of which personal records are made.

And PRs are nice. As nice as achieving a time goal or placing well in a race. They’re all very rewarding, socially sanctioned measures of success. But efficiency is more than a means to a speedy finish. To have raced efficiently is to have raced smartly—a tremendous achievement regardless of finishing time. And, while a race result may be affected by uncontrollable external factors, a smartly run race is a success we don’t have to share with the circumstances of the day.

Let’s not get too carried away with the word “smart,” though. I doubt if anybody who’s ever signed up for one of these events has thought, “Oh yeah, that’ll score me some IQ points.”

Take that race I was narrating in italics earlier, the one with all the falling and the nausea and the sleeping in the woods. I traveled 100 kilometers on foot (and butt—oh, so much traveling I did on my butt) to get to the place from where I started. In the process, I: almost got blown off a ridge, twice; invented and consumed unspeakable combinations of snack foods; chased a half orange down the trail and then ate it; got a bruise on my forehead because I sleepwalked into a tree branch. I’m not even a cartoon character.

I should really finish writing that race report.

An out-and-back? More like out-and-backbreaking. A point-to-point? How about point-to-pointless. Don’t even get me started on those looped races. Ultras are utterly and demonstrably wackadoodle.

◓ ◑ ◐

But seriously, they’re great. I would definitely rather do ultramarathons than not do them. If it’s the choir I’m preaching to on the other side of this newsletter, forgive me for calling your sport wackadoodle. And if you’ve never done an ultra, I promise I’ll try to lure you in some other time. For now, this is just going to be about the value of effort.

it’s sweat you won’t regret

As I was saying, ultramarathons are positively foolish endeavors. They’re a ginormous time suck (more so if you count the training for them), an unnecessary strain on the body (more so if you count the training for them), and frustratingly indefensible before the tribunal of familial skepticism at holiday gatherings (but you tolerate it because all those socks you got for Christmas will last you hundreds of miles).

Woven within this time-sucking, body-straining, indefensible foolishness is an intriguing proposition, the significance of which often goes unnoticed: We can still do the dumb thing smartly. The efficiency I talked about is nothing if not an exercise for the brain—an outstandingly well-rounded one, I might add. Okay, but why does this matter?

Because it means the doing is worth much, much more than the thing being done. It puts effort above ambition, smartness above circumstance, purposefulness above finishing time.

On those terms, if we choose to accept them, success is defined differently. Even if it doesn’t fit the objective definition, it only needs to matter to us. It’s like those socks you got for Christmas. The most humdrum of presents, the stereotype goes. But if you’re into running, or sock puppetry, well! There’s a greater-than-average chance Uncles Peter and Larry and Aunt Carol got you some great gifts. The point being: hosiery is subjective, and so is success.

It may come in many and unexpected forms, sometimes even before the finish: a slayed fear, a triumph over a doubt, a quiet epiphany, a new experience. We may not always recognize it immediately if it’s not staring at us from our list of predetermined goals, but whenever it comes, however it manifests, it will come from effort, and smartness, and purposefulness.

And since it’s so deeply ours, our success will sometimes have a distinct way of speaking to the senses—a scent, a sound, a texture. For me, as I stood on that podium with my trophy, success was shrouded in cold, damp, evergreen-tinted darkness. It rustled softly and smelled clean and resinous, a hint of petrichor betraying a rainfall, either recent or imminent.

all the bedding i need, right under my feet

When last we left me, I was battling the sleep monster for control over the cement blocks that were my eyelids.

I was so tired and loopy that I had started to veer off the trail and bump into trees. I was alone in a foreign land, hundreds of miles from my bed and still hours away from the finish, trying to find one place in this godforsaken forest that wasn’t spinning so I could close my eyes just for a little bit and try to sober up. It was 3:13 in the morning when I finally gave in.

“Would the cold wake me or cause me to sleep forever?” I’d never taken a nap on the side of the trail. At aid stations, around people and fire—sure. But never alone in the woods (in bear country, no less).

Self-consciously, as if somebody was evaluating my nap-taking performance, I chose my spot—not here, that’s an anthill, there—arranged my poles into an arrow on the ground, pulled my jacket’s hood up and its hem down, and sat in the cold, spongy dirt. After a moment, I turned off my headlamp, folded myself into the most compact shape I could, and then just… lay down. As if my bed had always been this cold and spongy. As if the forest had always been home. A strange moment, in equal measures pitiful and proud.

My eyes closed the second I heard the soft sibilance of pine needles on nylon next to my ear. My legs relaxed immediately, all too content to form the lower half of my fetal appearance. My whole body became weightless, the way the body sometimes does when one is ready to part with consciousness. I disappeared.

Seven minutes for the ground and the air to suck up my warmth and replace it with shivers. I got up, collected my poles, and started marching in the direction they had been pointed in, grateful I was going uphill and would soon warm back up.

◑ ◐ ◓

It’s fitting they call it a dirt nap. So unassuming and honest and cheap. A jarring oddity in my plushy, bedsheet-covered, detergent-scented life.

Yet, it did come at a price. I paid for it with 22 of my hours. An all-in effort, both mental and physical. My unconditional best on that day. Come to think of it, it’s the bedsheets that come cheaper.

As you already know, that effort turned out to be good enough for a podium spot (unsurprisingly, the snow had slowed everybody else down, too). It was the podium spot that wasn’t good enough for the effort. I kept the trophy, of course. It was a nice enough trophy of sturdy construction, sharp metal edges, and bold typography. Pleasingly tangible and universally validating. But what I wished I could take home instead was my cold, spongy mattress, with its intoxicating redolence and its whispering pine needles.

What makes a nap on the side of the trail more special than this polished piece of metal and wood so singularly emblematic of competitive success?

Perhaps the fact that it was my first nap on the side of the trail. And, like many other firsts before it, my sleeping in the dirt was an eye-opener (*chuckles at own pun*): sometimes, the comforts I actually need get mixed up with the comforts I seek blindly out of inexperience, lack of confidence, or the facile inertia of habit.

Silly as it may sound, the moment I made the decision to take that nap was the moment I graduated multi-day-ultra school. It no longer mattered how long a race was or how scattered the aid stations—I could sleep on my own time. All I needed was the ground under my feet.

A rustling purveyor of independence. A cold and spongy gateway to bolder adventures. It’s a brave new world indeed when bedding need not come with a thread count.

That’s what I bought with my effort: a brief flare of clarity illuminating a newly gained self-sufficiency.

ius triumphi

So, was my race successful by objective criteria? On the one hand, I did finish, and there’s the big whoop of being among the first to do so. On the other, this was my slowest 100k ever, during which I fell down (and -apart and -asleep on my feet) too many times to count and dry-heaved through the entire night and part of the morning. And I believe I mentioned the passive-aggressive tree branch—that sucker left a visible mark on my forehead. I guess it’s a toss-up, then? Whatever. More importantly:

Was it worth the effort? You already know the answer, but here it is anyway, right after today’s Reading Recommendation in a Single Quotation with No Further Explanation:

❝And I realize anew […] that, much as I love my sport, it is somewhat weird. Who but an idiot would race 26 tortured miles plus 385 yards for the dubious distinction of finishing 38th?

—Ray Charbonneau, The 27th Mile

Hell yeah, it was worth the effort. That silly little nap was.

I do appreciate my trophy—in no small part because it’s one of a scarce few to grace my closet’s top shelf. But I’m grateful for it for another reason, as well: Without it, proving the value of effort over end result would’ve been left to the ol’ “sour grapes” approach. Now that I have the grapes in my possession, I can say without any doubt that, while they’re certainly not sour, reaching out to grab them was much sweeter.

Or, if you prefer the grape-free radio edit: It’s not about the thing; it’s about the doing of the thing.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed your time here, please share “‘To Choose the Effortful Way’ (and Let Success Be Defined by My Effort)” or this newsletter with a friend. Then go see if you can catch a falling leaf.

I've yet to try the mid-race dirt nap, but I should probably add it to the toolkit (I have witnessed their magic, though, pacing a friend who makes them a regular part of his 100-mile plan). Thanks for the post (and congrats on the trophy).

Which 100K was it? I love your “point to pointless” phrase!